The emblematic proboscis monkey (Nasalis larvatus) is a primate endemic to Borneo.

Photographed on Bako Island, the Wagler’s Pit viper (Tropidolæmus wagleri) is a tree-dwelling snake that is fatal to humans. It belongs to the Viperidæ family.

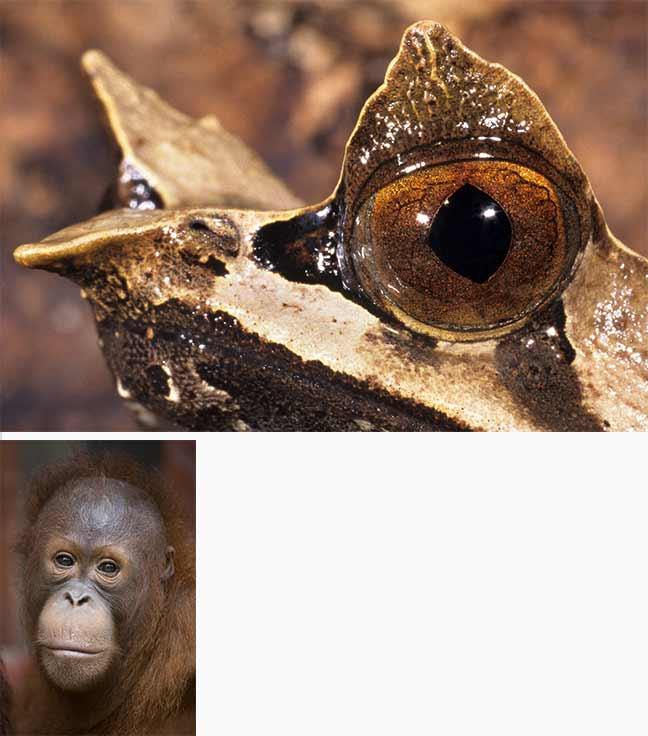

Amphibians in the Borneo tropical forest are discreet by day, and easier to observe by night.

A male wrinkled hornbill (Aceros corrugatus)

It belongs to the Bucerotidæ family

Borneo pygmy elephant (Elephas maximus borneensis). A victim of deforestation, it has been put on the list of endangered species by the IUCN.

Reptile of the Agamidæ family (Gonocephalus bornensis).

In two years, six million hectares of primary forest have been felled.

Fruit of the oil palm (Elaeis guineensis).

The silvery langur (Trachypithecus cristatus), also called the hooded Semnopithecus, prefers the mangroves on the edge of the tropical forest.

Meeting with a Wagler’s Pit viper (Tropidolaemus wagleri). Photo Dany Grahek

L’arche Photographique

Itemise and inform

Journey to Borneo

Borneo: Hell in Paradise

Delighted as much as repelled: that is how I felt on my return to Borneo. The island covers 740 000 km2, and it is shared between Indonesia (which occupies 4/5 of its territory), Malaysia, and Brunei. Borneo is the setting for what nature offers that is most beautiful, and for what humans have done that is the stuff of the worst nightmares.

Bako National Park

First came the delight in Bako National Park, in the state of Sarawak (Malaysia). I went on foot through the tropical jungle in all its richness and exuberance. All was luxuriant. I felt the density of the plant mass that surrounded me like the very burgeoning of life itself. I was walking through an encyclopædia of the living world! The famous biodiversity about which we are constantly told was right there, around me, in shapes and colours.

There are no fewer than 150 species of birds in the park, and lots of reptiles. I was very surprised the number of snakes that crossed my path. It is one of the last refuges of the proboscis monkey, which is threatened with extinction.

In the mangroves, those inextricable forests that grow with their roots in water, I happily observed dragonflies, mudskippers, and the silvery langur, a monkey with metallic grey fur of which the young are born red-furred, greatly at ease in the impenetrable aerial roots of the mangroves.

The spider (Heteropoda sp) protects its egg in a silk cocoon. The cave-dwelling species measures 20 cm in length.

Night walk

The night held even more surprises for me. I went on several “night walks” to observe the species that go about the forest after sunset – and such activity! Tarsiers (tiny primates with globular eyes), flying lemurs, bats, impressive spiders, liana snakes, lizards, and amphibians in abundance…

The pyrops (Pyrops whiteheadi) sucks up tree sap thanks to a very pointed appendage that can pierce bark.

Using my headlamp, I observed surprising number of insects. I found one of them particularly charming: the splendid Pyrops whiteheadi, with yellow-spotted wings from which rises a strange head in the form of a turquoise trunk! On returning from the night walks, my eyes were full of pictures and my legs were covered in leeches. Back at the camp, I removed one by one those Borneo tiger leeches that play at clandestine passengers.

The Kinabatangan River

My reportage also took me to Eastern Borneo, along the Kinabatangan River, a hotspot of biodiversity. To visit that ribbon of water that slithers along 560 km at the very heart of the tropical jungle, between marshes and primary forest, there was no choice other than a small motorboat piloted by a local guide, who knew how to navigate the river’s branches to go ever deeper into the jungle.

The Kinabatangan Rivers crossed the tropical forest before flowing into the Sulu Sea.

In that enchanting Eden, all that was needed was to switch off the motor and allow oneself to slide silently to draw near to animals that were quite unafraid. It is the domain of the last of the pygmy elephants, which are also threatened with extinction. I was fortunate to photograph a small herd on the riverbank.

In the skies, rhinoceros hornbills, kingfishers, and anhingas put on a show. In every direction are things that crawl, fly, and climb, whilst cries and songs rise out of the tick vegetation…

The Danum Valley

Another detour via the Danum Valley, a protected area in the state of Sabah (Malaysia) that is home to a number of scientific research centres. That setting in a humid tropical forest, where you could think yourself back in the middle of the Jurassic period, is the last home of the Sumatran rhinoceros, of which here are not more than fifteen individuals in the wild, and of the clouded leopard, with its stunning markings.

Liana serpent (Ahaetulla nasuta) in a tree.

For me, it was also the setting for a memorable fright! In the dense forest, as we were following a rutted track aboard an old pick-up truck, a loud cracking sound tore through the undergrowth, right near our vehicle… The driver stopped the vehicle immediately. We all looked in every direction, and all of a sudden, just 20 m ahead of us, a huge tree trunk came crashing down! It could not be overcome. We could not cut it up to pass through it – that would take hours. Finally, another vehicle reached us from the other side – but to reach it, we had to climb through a tangle of inextricable branches.

The assault of oil palms

Right by those marvels was the carnage that I discovered whilst flying over Borneo in an aeroplane. A few decades ago, the island was over 90% covered by tropical jungle. Less than half is left. From a little height, I got a sense of the extent of the massacre. Stretching out of sight and covering hundreds of square kilometres, oil palms are lined up like soldiers in a North Korean military parade. A plant desert of lined-up clones has replaced the burgeoning life that animated the primary forest in the same place, a few months previously, and of which there remain, here and there, a few islets that have been spared, surrounded by the invading palms. Extermination that is at once terrifying and saddening.

The oil palm comes from Africa, and represents an enormous financial benefit for the multinationals of the agro-food sector. Therefore, I invite you to boycott all the products made using palm oil or its derivatives.

On the ground, I observed that those plantations had chased away life. I observed very few birds and no other animals. It was difficult to bring back pictures, because on the site, the people running the plantations and the workers made me understand that they did not want any photos.

A little bit of forest in our chocolate bars

There is one obvious question: what is the use of all those oil palms? They produce palm oil (often coyly described as “vegetable oil”), which is found in a multitude of products in daily life (almost one in ten!): biscuits, breakfast cereals, sauces, crisps, chocolate bars, frying oils, shaving gels, other cosmetics, etc.

Indonesia has become the world’s leading producer of palm oil. That industry is vastly more profitable in the short term than the tropical forest and its biodiversity, so there is no question of stopping – on the contrary: in two years, six million hectares of primary forest (original, i.e. the richest in biodiversity) have been felled; that is an area almost as big as Ireland. Over 20 years, the area covered by palm groves has increased 27-fold. That is not the end of the matter: the country intends to increase oil production by 60% by 2020.

Great apes in souvenir shops

The consequence in Borneo is that its biodiversity is in freefall. The habitat of all those unique, admirable species is being directly destroyed. They have nowhere to go - certainly not the palm plantations, where they are killed.

The deforestation caused by intensive palm-oil production is one of the main causes of the decline in the population of orang utans (Pongo pygmæus).

There remain between 45 000 and 69 000 orang utans (less than 15% of the original population), decimated by hunting and deforestation. For proboscis monkeys, the last estimate – which dates back to 2007 – counted fewer than 7 000. For how much longer will the orang utans, proboscis monkeys, and all the marvels and strange things that I photographed survive?

Photo advices

For this adventure, you must travel light, because there is a lot of often difficult walking in the jungle and the mangroves. Do not neglect macrophotography equipment, because on this type of journey, close-up photography accounts for over 50% of all shots.

Be careful

The climate is very humid. When you take breaks, leave your equipment in the sun for a few minutes to avoid mould growth.

Equipment

2 full-frame digital reflex cameras.

- 1 wide-angle zoom lens 24 - 70 mm f/2.8.

- 1 zoom lens, 70 - 200 mm f/2.8.

- 1 telephoto lens, 300 mm f/2.8 + 1 extender x 1.4. A focal length of between 300 mm and 420 mm is largely sufficient for the region’s primates and birds.

- 1 macro lens, 100 mm f/2.8. A 180-mm or 200-mm macro lens may be useful for increasing minimum depth of focus when taking close-up shots of Borneo’s venomous snakes.

- 1 set of extension rings. Very useful for small insects.

- 1 double macro flash. Essential for this journey. In the tropical forest, reptiles, amphibians, and insects are most active at night.

- 1 monopod is enough if you only take pictures. A tripod is essential for videomakers.