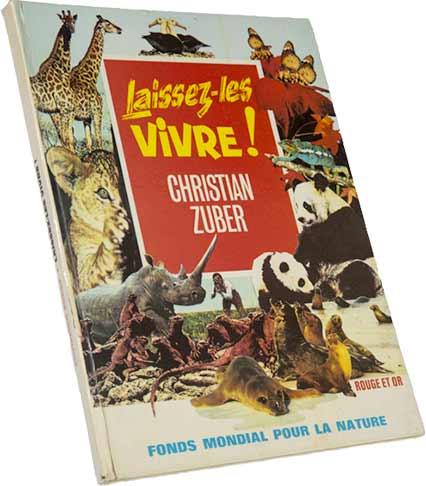

Christian Zuber’s book Laissez-les vivre (Let Them Live), published by Rouge et Or in 1970

Christian Zuber is convinced that “information will save nature”. Hence, he gives numerous lectures at which his films are received with great success, writes books of which some are aimed at children, produces records of traditional music and songs.

Mountain gorilla in the DRC

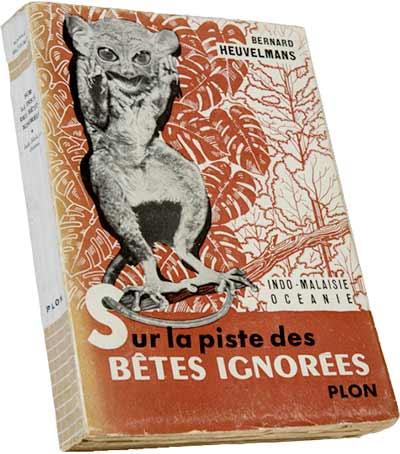

Sur la piste des bêtes ignorées, 1955, by Bernard Heuvelmans

the work enjoys great popularity with almost one million copies sold, according to Jean-Jacques Barloy.

Thereafter, Heuvelmans wrote books on large sea animals living at great depth (Dans le sillage des monstres marins (In the wake of sea monsters), 1958) before working with the Russian historian Boris Porchnev to co-author a book on crypto-anthropology entitled “L’homme de Néanderthal est toujours vivant” (“Neanderthal Man is still alive”) in 1974

Beware! Crossing point for dromedaries, wombats, and kangaroos (Australia)

The egg-laying of the black-necked grebe

L’arche School

Educate and make aware

7 questions on animal photography

Young people whom I meet at nature-photography festivals, during photography training sessions, and in the field often ask me the same questions. Those questions relate to the profession of photographer, the lives of animals, and the future of biodiversity. This section is an attempt at giving some answers!

What made you want to become a professional animal photographer?

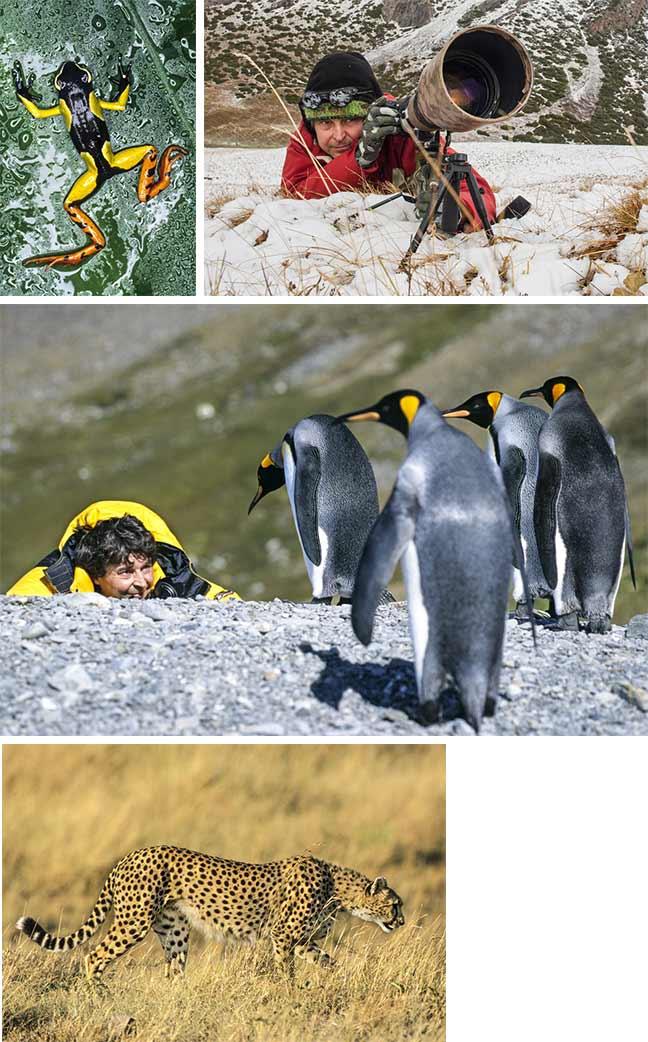

Before thinking about photography, I was passionate about wild animals. When I was a teenager, I would borrow my grandmother’s theatre glasses to go bird-watching and to try and identify the birds I saw. One fine day, my parents bought a black-and-white television set. My passion continued to grow thanks to that box of dreams, on which I watched animal films made by Frédéric Rossif, the adventures of Christian Zuber, and the documentaries of Lieutenant-Commander Jacques-Yves Cousteau. Captivated by the screen, I was fascinated by all those images… and at the age of 11, I had made my decision: I would become an animal filmmaker.

However, as is often the case, life decided otherwise, and it sent me in a quite different direction. I was not a very good student, I failed my school guidance, and I had to start earning my living rather early. That is how, at the age of 19, I found myself in the world of work ads a dental technician. I was very far from my childhood dreams – but they were still present! I very quickly felt that being a dental technician was not right for me, and that it was not the life I wanted. I had to get out! It took me a good ten years to leave that annoying universe and finally find the work in which I realised my potential, work that combined my three passions: nature, photography, and travel.

My love photography also has its roots in my childhood. When I was very young, I would go with my father – who was an amateur painter – to the banks of the Loire, where I would watch him paint. He it was who taught me to see nature as a work of art, to build an image, to understand perspective, to position myself relative to a subject… In painting, the rules of composition are very close to those of photography.

How does one become a professional animal photographer?

Being an animal photographer is a dream profession! That is perhaps why I am often asked that question. The truth is that each animal photographer has her / his own answer, because each one has followed a different path. There is no magic recipe for becoming an animal photographer; each one has to make up her / his own! However, some ingredients are essential for entering the profession

To begin with, and most obviously, you have to know how to take beautiful photos! To start and to learn correctly, you can go to a photography school – but learning the technique comes with practice.

Next, to photograph animals, you have to know the animal, its way of life, its habits, its habitat, its reactions… in short, you need good naturalist knowledge. That is acquired by discovering nature and observing it, as well as by reading naturalist books and guides.

That is not all. A good photographer must also know how to tell stories, find new ideas, and launch forth into untested concepts. Nowadays, in order to stand out, you need to show originality and to take artistic risks.

Finally, in order to make your work known, you must also be comfortable with the business side of things. That means being able to communicate, and being able to sell yourself. Like many dream professions, animal photography requires a lot of work, patience, and perseverance – as well as a large amount of luck… and all that comes naturally when you have a passion for it!

Can you make a living from your pictures?

The answer to that question has changed completely over the last few years. Ten years Ago, I would have said “Yes”. Now, my answer is a little more considered. You ought to know that in France, professional animal photographers who make a full-time living just from their work have become rare, and can now be counted on the fingers of both hands. All the rest, in other words the vast majority, are amateur photographers who have a sideline that brings in the money, or who have a pension that enables them to pay the bills.

What has happened since the golden age of photography in the 1980s to the 1990s, when photographers earned enough in copyright fees from the use and publication of their photos to say that they earned a salary? The main change has come about due to the move from analogue to digital photography. That move has meant that lots of people have taken up photography and have gone on to post their photos on the internet, where it has become easy to get large numbers of images pretty much free of charge. As a consequence, copyright fees earned by photographers have fallen sharply.

Nowadays, the relationship with photos has changed greatly. Social networks are flooded and saturated with images. Photo agencies and magazines offer very low rates. Other structures, called “microstocks” and often dealing in work produced by amateur photographers, offer images for just a few euros. To be realistic, the climate has become very difficult for anyone who wants to live off copyright fees. Because of that, my advice is to do animal photography as a hobby rather than as a profession. That said, we are each entitled to follow our own adventures! You just have to remember that the road is a long one, and that few are called to walk it.

What is your favourite animal?

I don’t have just one favourite animal; I have three and I can’t choose between them! My heart ranges between extremes: the dragonfly, the humpbacked whale, and the mountain gorilla. I have a soft spot for the dragonfly, because it was the subject of my first photograph. Those damsels in the air, fearsome predators, still fascinate me with their æsthetic, their lightness, and their unrivalled ability in flight. There is something fairy-like about them.

I also like the humpbacked whale, perhaps because its monumental size makes it so majestic. For all its size, it is the most playful and outgoing of all the whale species, and I am always impressed to see that mass surge out of the water and do spectacular jumps, an activity that is called “breaching”.

If I have to choose, I shall go for the mountain gorilla. I was fortunate to be able to photograph that animal in the three countries where it lives: Congo, Rwanda, and Uganda. When I observe the mountain gorilla, I feel all the power, serenity, and peace emanating from the animal. It gaze can also be disturbing – perhaps because it reminds us that we are close relatives.

Is there an animal that you have never photographed and that you dream of photographing?

Yes. There are photos that I shall doubtless only take in my dreams! Let me explain. When I was about 15, I was in a second-hand bookshop. By chance, I came across a book called “Sur la piste des bêtes ignorées” (“On the trail of unknown beasts”). Carefully covered in glassine paper, the work straightaway aroused my curiosity. It was a book by Bernard Heuvelmans, the best-known crypto-zoologist, one of a group of researchers who are interested in animals that have disappeared or are unknown, and of which the existence has never been formally proven.

Drawn in by the promising title, I immediately bought the work. It has been published in about the mid-1950s, and told of mysterious, disappeared, or unknown creatures that could still be alive in our time in remote areas of our planet. Bernard Heuvelmans’ books made me dream for a number of years. I saw myself as a bold adventurer at the head of an expedition, exploring the dense jungle of a forgotten land… after weeks on the march, I suddenly found myself face-to-face with an unknown animal species! Of course, thanks to my Beaulieu 16-mm camera, I took back to civilisation a film with exceptional pictures that would go around the world.

Those heroic visions have remained unrealised to this day … but they inspired one of my first great journeys, called “Expédition Thylacine” (“The Thylacine Expedition”), the aim of which was to go to a remote region of Tasmania to look for a species that had become extinct in 1936: the Tasmanian tiger (also called the thylacine, or marsupial wolf). When I got there, I found no trace of the animal, but at the time, that great adventure enabled me to get my foot on the ladder, for I won the first prize of the Kodak Grand Reportage award.

All these later, I am still fascinated by those mythical species that are observed from time to time. In spite of a few hoaxes, the reports made by travellers and natives are often based on fact. In any case, I still want to believe, and I even have a few ideas in the back of my mind. So it is that one of these days, I may try my luck once more by mounting a fresh expedition to look for an animal that is no longer with us!

Of all the countries that you have been to, which is your favourite?

My photographic journeys have taken me to every continent, and have enabled me to discover the incredible diversity of natural habitats on the surface of our planet. The country that I like best is the one that contains almost of that in itself: Australia.

It has deserts, savanna, temperate forests, tropical forests, mangroves, mountains, islands, etc. It is a concentrate form of nature in all its forms. In addition to that diversity, Australia has a lot of originality: the animals, such as the marsupials, are very different from their fellows on the other continents.

Finally, what I like there the immense spaces with very little in the way of human population and where nature reigns as master. Australia is a little bit like Paradise for a nature photographer!

What is your best memory of an animal photo?

I did not have to go to the ends of the earth, to experience my greatest photographic emotion; I did so right near where I live. I was doing a photo shoot on the ponds of the Brenne Natural Park, which is in my area. For months, I spend hundreds of hours concealed in my floating hide, a hideaway made up of camouflage cloth mounted on a float. I entered it early every morning, and sometimes stayed in it until sunset.

The black-necked grebes were in the middle of their nesting season. I found a nest hidden amongst the water lilies, well exposed to light. On that day, the female and the male were particularly agitated. They were going to and fro to take vegetation to the nest. I thought that they feared the presence of a predator, but such was not the case. In reality, the female was getting ready to lay her egg! The egg took a few seconds to emerge, and in that time, I took pictures at lightning speed: nine shots, not a single one more. That was enough to immortalise the magic scene: a female black-necked grebe laying an egg! A “scoop” that would be seen in magazines around the world.