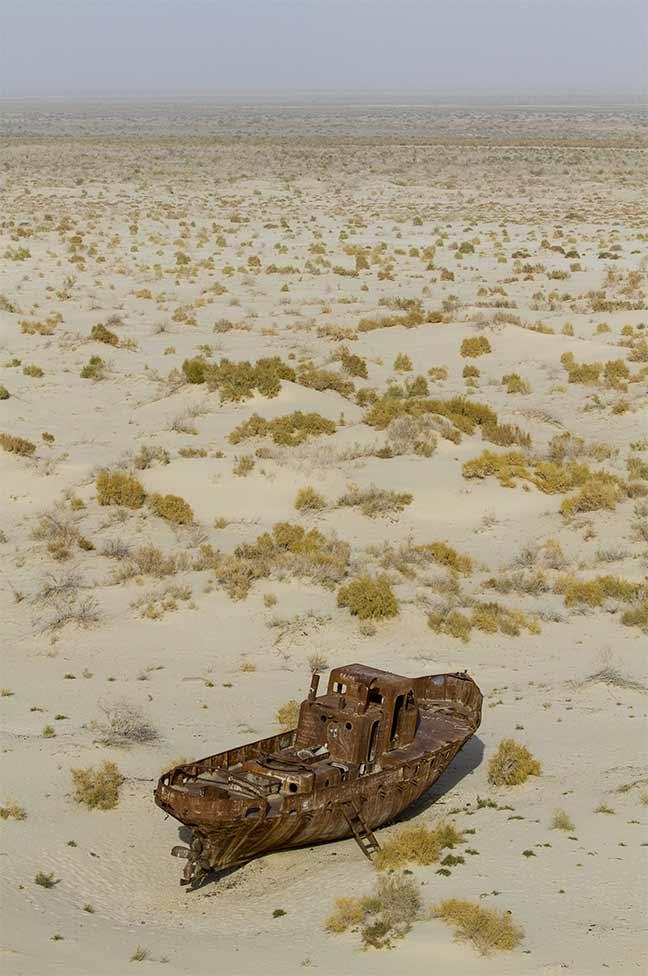

The wrecks which lay strewn on the dried up bottom of the Aral sea are regularly plundered by scapmetal dealers.

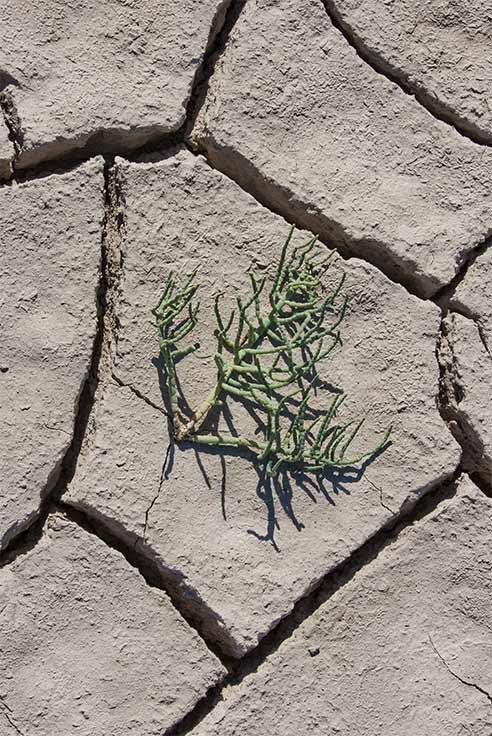

The salinisation of grounds increases a little more every year. Every month, 600 km² of arable land disapear from the surface of the earth.

After 80 km of track, a first sign of life: this beetle roaming under a blazing sun.

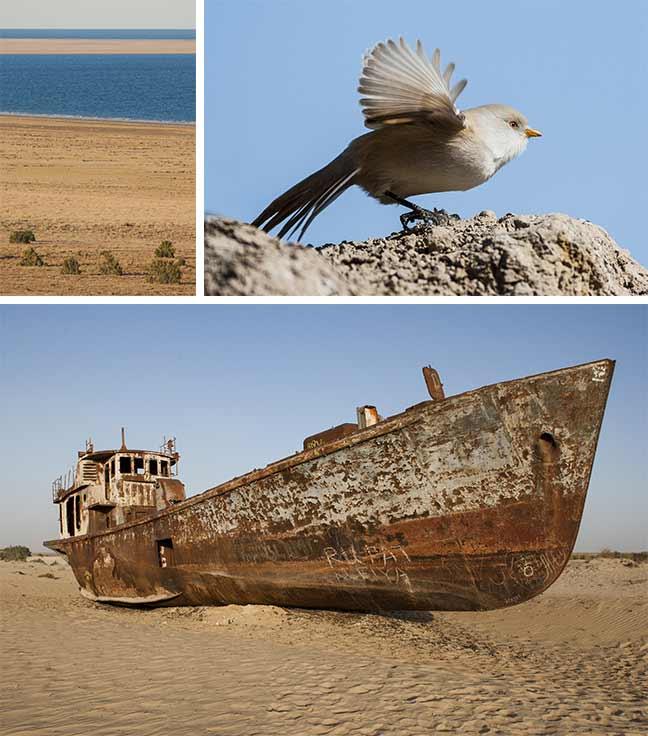

Wreck of a fishing boat abandoned near the former port of Moynaq.

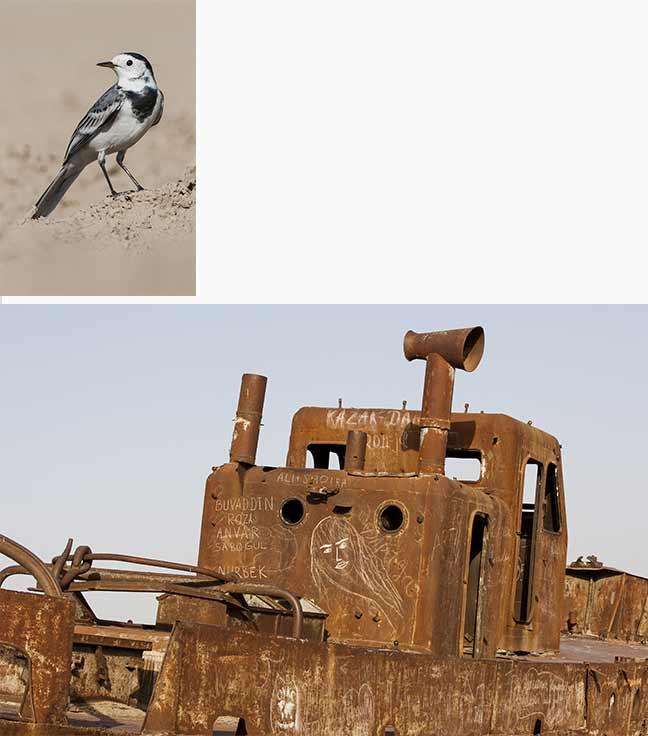

In the heart of the desert, a pleasant surprise: a marsh which shelters an avifauna.

Decoys left by poachers.

Several gas and oil companies have settled in the drained heart of the Aral sea.

In the dry bed of the Aral sea.

L’arche Photographique

Itemise and inform

Journey to the Aral sea

The Aral sea: a foretaste of the apocalypse

On my way to photograph the snow leopard in Kirghizstan, I did not think that the story would take me to Tashkent, capital of Uzbekistan, for a quite different adventure. One additional flight and a few hours on the road saw me in Karakalpakstan, looking for the last bits of spray from the Aral Sea.

Quays on the edge of a sea of sand

Moynaq is the last settlement before the desert. That is where I found two local guides to accompany me, and to buy all the victuals and other supplies needed for the camps – for after the city, there is nothing. Nothing more than memory. Moynaq was once a prosperous port, one of the USSR’s fishponds, living to the rhythm of the comings and goings of the trawlers and processing 20 000 tonnes of fish per year. The population of 60 000 inhabitants lived off the fishing and canning industry.

Today, the roads lead out into the desert, and the shoreline of the current Aral Sea lies 180 km away. The town has been forgotten by the world. It is ravaged by winds that carry sand, salt, and dust. It is difficult to imagine the life that enlivened the place, now a ghost town, depressing and lugubrious, almost deserted since the 1980s, where human misery is rampant. Only the old photos in the local museum bear witness to its flourishing past.

Like a tap that has been turned off

In the 1950’s, the Soviet regime focused on the intense development of cotton cultivation. To irrigate the desert steppes, water was taken from two large rivers, the Amu Darya and the Syr Darya – the two rivers that flowed into the Aral Sea and enabled it to make up for intense evaporation in that region of Central Asia.

In 1950, The Aral Sea covered an area of 67 000 km2. At the time, 173 animal species were counted along its coastline. Today, just forty have survived.

The balance was upset. In 1980, the flow was only one tenth of what it had been in the 1950’s. The sea began to lose more water than the rivers poured into it. From 1966 to 1993, its level fell by 16 m and its shores retreated by 80 km. It lost 90% of its volume and three quarters of its area.

Sea and phantom ships

Fishing vessels abandoned by their idle crews were grounded one after the other. Worn down by winds of sand and salt, picked apart by the pillagers who try to recover the steel plates. Like leaves chewed by ants, their rusty hulls also disappear inexorably from a landscape that has been desertified, and where the vessels’ presence gives an air of the end of the world.

In the 1960’s, the fishing industry in Moynaq and Aralsk processed 20 000 tonnes of fish each year.

Right in the middle of post-apocalyptic science fiction

Driving along a seabed is an experience that is out of the ordinary… Right in the middle of the desert, I said to myself that just 50 years ago, there were several tens of metres of water above my head, teeming with marine life, banks of fish and plankton, and criss-crossed by fishing vessels. I raise my eyes. To the sky. Today, sandstorms sweep the temporary trails of this immense sandy basin that no longer contains anything. I tremble on realising what human folly can do: empty a sea!

Bearded reedling (Panurus biarmicus).

To add to the terrifying scenario, the region has alarming rates of kidney and respiratory diseases, cancers, tuberculosis, and congenital deformities. They are caused by the chemical fertilisers and pesticides that were used in massive amounts for growing cotton, and which seeped away to be deposited in the seabed sediments, where they were forgotten. As the sea evaporated, the deposits came back to the surface, carried along by winds and dramatically affecting the health of the population. Who could foresee that people would one day breathe in the poisoned seabed of the Aral Sea?

Encounters of the third kind

Aside from the austere bushes that have colonised the sand, there are no birds to be seen, no animals in this ecosystem that changed in just a few years from marine to desert. Life has fled. But perhaps not so far away… Driving along the seabed, we stopped to eat. And there, in the middle of nowhere, on a bed of crushed shells, a large beetle was walking along nonchalantly. A touch of hope on the remains of the drama?

Mute swan (Cygnus olor).

Another encounter of the third kind awaits us – and it is less pleasant. Below an escarpment that lies along the basin once occupied by the sea, we discover a wetland that forms a mosaic of ponds and reed beds. They are the last freshwater marshes fed by the Amu Darya. For a moment, I found myself back in France, in the Brenne or the Camargue. The similarity is even more troubling with the presence of mute swans, common pochard ducks, red-crested pochard ducks, Eurasian coots, and several passerines. In the devastated area, this noisy oasis of life is unexpected, as though a parallel reality.

All of a sudden, there is a long moment of fight and disarray. In this peaceful Eden set beside the disaster, I hear gunshots. There I am, nose to nose with… hunters! German tourists caught in the midst of their hunt. It induces despair. How can one kill birds for pleasure in that fragile scrap of nature saved by miracle? Ransack life right where it struggles hard to survive.

A glimmer of hope?

Some of the countries that share the Aral Sea are trying to save what remains of it. the level of the northern part (the sea has been split in two since 1989), which is fed by the Syr Daria, has remained steady since 2005 thanks to the Kok-Aral Dam built by Kazakhstan.

Unfortunately, the ecological catastrophe of the Aral Sea is not an isolated case. In Kazakhstan, Lake Balkhash is suffering the same fate.

Uzbekistan is the world’s second-largest exporter of cotton; it has done nothing to reverse the scenario – and there is worse to come. I learn that the Uzbeks have sold the dried-up seabed to Chinese and Malaysian companies that are carrying out soundings and that are drilling to reach the gas and oil trapped in the sediments of the former sea. Derricks and pipelines add to the tragedy. The sea has been emptied of all life, and now its bottom is being stirred up in search of fossil fuels. The Aral Sea has died twice.

Photo advices

Visiting the Aral Sea requires a 4 x 4 vehicle. There is very little walking, so there is “no limit” on the weight of photographic equipment.

Be careful

In the desert that the Aral Sea has become, there are frequent strong sandstorms that throw up very fine dust. Carry watertight plastic bags and neutral filters to protect your lenses.

Equipment

- 2 full-frame digital reflex cameras.

- 1 Ultra wide-angle lens 15 mm f/2,8.

- 1 wide-angle zoom lens 24-70 mm f/2.8.

- 1 zoom lens 70-200 mm f/2.8.

- 1 telephoto lens 500 mm f/4 or zoom 200-400 mm f4. The fauna observed in the Aral sea is rather wild. If you can, take an extender X1.4 or X2.

- 1 standard flash.

- 1 tripod for landscape photographs and video.